Beyond Opposites: Rethinking Ju and Go in Aikido Philosophy

Ju 柔 (Softness) and Go 剛 (Hardness) are terms frequently used in martial arts. Conceptually, we often refer to a martial art or style as being “soft” or “hard”, but is this a meaningful or accurate expression? What are the true meanings of 柔 and 剛?

Before diving into the details, let’s start with the question of whether it should be written as 剛柔 (Go-Ju) or 柔剛 (Ju-Go). Historically, 剛柔 is the more traditional and commonly seen order in Chinese classics and early Japanese literature. This form appears in ancient political and philosophical texts, such as Confucius’s Zhong Yong 中庸 (The Doctrine of the Mean) and the military treatise The Art of War 孫子兵法. It remains the standard expression in Chinese culture today. In contrast, modern Japanese budo, particularly post-Meiji, often uses the order 柔剛. A well-known example is the phrase 柔剛一体 “Softness and Hardness as One”, frequently attributed to Jigoro Kano 嘉納治五郎, the founder of Judo.

Karate is generally seen as a “Go” style of martial art

In Asian culture, the order of terms carries subtle implications. The use of 剛柔 in classical Chinese thought suggests a philosophical starting point rooted in strength or authority, balanced afterward by gentleness or adaptability – especially in rulership and governance, a concept that naturally extended into martial discipline. The Japanese preference for 柔剛 reflects a shift from militaristic frameworks toward spiritual self-cultivation, where one begins with softness and inward reflection, gradually developing internal strength. Linguistically, both arrangements have no problem; the choice of which to use depends on what is being emphasized. For most people, it’s also a matter of historical tradition or stylistic convention.

Tai Chi is a classic “Ju” style of martial art

Chinese characters, or kanji 漢字, often carry rich and layered meanings. “Softness” and “hardness” are basic translations, but they may not fully capture the depth of 柔 and 剛.

柔 literally means soft, gentle, and flexible. In oracle bone script 甲骨文 and ancient bronze inscriptions, the character is composed of 木 (wood) and the phonetic element 矛 (spear). The wood component suggests pliability – something that bends and flows without resistance, yet does not break. It symbolizes the quality of non-rigidity and adaptability. In martial arts, 柔 is not weakness, but rather the adaptable, efficient, and ingenious use of force

剛, by contrast, means hard, firm, and strong. Etymologically, the character combines 岡 (mountain ridge) with 刂 (knife), symbolizing a strong, sharp, and resolute quality. In martial contexts, 剛 does not refer to brute or mindless force, but rather to unyielding power, controlled explosiveness and uncompromising intent.

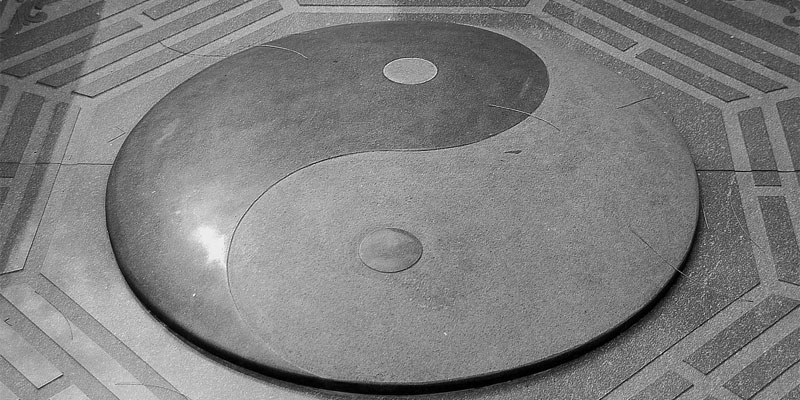

Philosophically, 柔 corresponds to Yin 陰, and 剛 to Yang 陽. Therefore, there is no inherent superiority in one over the other, they are not opposites but complementary principles. Their application is context-dependent, and mastery lies in knowing when to use one to counterbalance the other. A modern Japanese phrase beautifully captures this dynamic:

「柔よく剛を制す、剛よく柔を断つ」

“Softness can overcome hardness, and hardness can cut softness.”

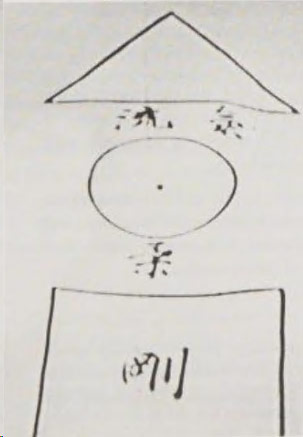

Sangen – Ki Flow 気・流 , Softness 柔 and Hardness 剛

Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido, interpreted 柔 and 剛 through the lens of his understanding of the universe, Shinto cosmology, and love. He did not merely see them as opposing technical forces, but emphasized their unity and harmony. He related 柔 and 剛 to the Shinto concept of Sangen 三元, in which both are born from Ki・Flow 気・流. When these three elements are in alignment, they give shape to the entire cosmos. In Ueshiba’s cosmology, 柔 and 剛 are inseparable, and this unity must also be reflected in his Aikido. Some accounts suggest that pre-war Aikido training began with a more direct, physical expression of 剛, gradually transitioned to 柔. Regardless, Ueshiba believed that true Aiki could only be realized through the harmonic balance of the two.

In modern times, due to differences in eras, safety considerations, or even marketing strategies, mainstream Aikido has often leaned toward emphasizing 柔, or at least this is how it is often portrayed. The English translation of 剛 as “hardness” may have also contributed to misconceptions, as “hard” can evoke a negative image of stiffness or brutality – qualities not aligned with the true martial 剛.

Thus, how to preserve and present the essence of 剛 within Aikido has become an increasingly relevant topic in both training and transmission. While a full exploration of this subject is beyond the scope of this article, it is a question well worth contemplating for any serious Aikido practitioner.

Related reading: Sangen – The Triangle, Circle and Square in Aikido

Author’s Note: We appreciate your readership! This article serves as a preliminary introduction to the subject matter. While we aim for accuracy, we cannot guarantee the content’s precision and it may contain elements of speculation. We strongly advise you to pursue additional research if this topic piques your interest. Begin your AikidoDiscovery adventure! 🙂