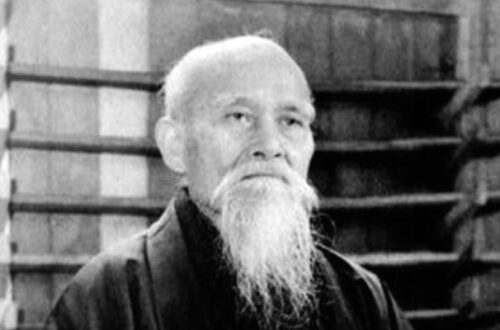

Morihei Ueshiba, Onisaburo Deguchi, and the Second Omoto Incident

The Second Omoto Incident 第二次大本事件, which occurred in 1935, was a significant event in Japan’s modern history, involving the suppression of the Omoto religion by the Japanese government. Founded by Nao Deguchi 出口直 in the late 19th century, the Omoto religion combined elements of Shinto 神道 and other beliefs, promoting peace and universal harmony. It was led by Nao’s son-in-law, Onisaburo Deguchi 出口王仁三郎, a charismatic figure with ambitious visions for world peace and universalism. Omoto attracted followers nationwide; however, the religion’s perceived unconventional teachings and political influence attracted the scrutiny of the Japanese government, which led to the first major suppression in 1921, known as the First Omoto Incident 第一次大本事件.

Morihei Ueshiba, a dedicated follower of Omoto, had a very close relationship with Onisaburo. After the First Omoto Incident, he worked closely with him to help rebuild the religion. In 1924, Morihei accompanied Onisaburo on a failed expedition to Mongolia with the ambition of establishing a new religious kingdom there. Despite the failure of the journey, Omoto’s popularity grew, partly due to the media attention it received from the expedition, and Morihei’s reputation as a martial artist was also enhanced. Onisaburo continued to proselytize, organizing religious allies from countries such as Korea, China, and Germany, to promote universal brotherhood and world peace. According to the second Doshu, Kisshomaru Ueshiba, Onisaburo began isolating Morihei from activities directly related to Omoto out of personal kindness and consideration, likely in response to the previous suppression. While Omoto continued to expand, Morihei moved to Tokyo in 1927 to teach Aikido in response to invitations from Earl Gonnohyoe Yamamoto 山本権兵衛伯爵 and Admiral Takeshita Isamu 竹下勇大将.

Onisaburo Deguchi’s creation of raku pottery, published in Omoto’s official magazine in 1926

In the following years, Omoto continued to gain momentum by holding exhibitions, lectures, and film screenings, and even acquiring media for proselytizing. This attracted a large following, including many high-ranking officials. However, Japan’s political climate was increasingly nationalistic, authoritarian, and militaristic as the country pursued imperial expansion and cracked down on social groups that threatened its policies. Omoto’s teachings on peace and ideals that sometimes conflicted with Japan’s imperial ambitions, along with its perceived criticism of the government, made it a renewed target. In 1934, Onisaburo established the spiritual movement organization Showa Shinseikai 昭和神聖会. He starated criticizing the government’s response to domestic and international issues, and even called for the overthrow of the Okada Cabinet 岡田内閣. Later, he led 900 followers in a march from Tokyo Station to the Imperial Palace, severely criticizing the theory of the emperor as an organ of the state and promoting the concept of the “Sacred Imperial Way” 神聖皇道. This ultimately led to another mass crackdown on Omoto in 1935.

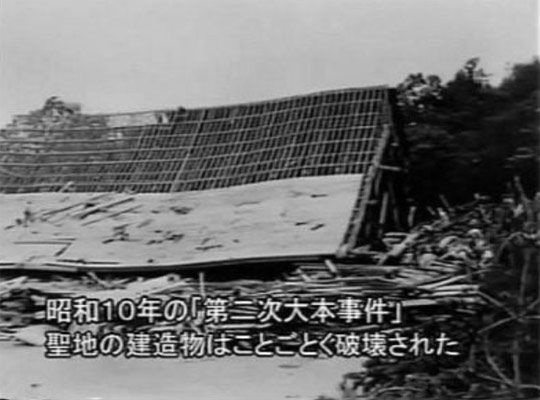

Building destroyed in The Second Omoto Incident

On December 8, 1935, hundreds of police were mobilized to the Ayabe 綾部 and Kameoka 亀岡 areas. Onisaburo, along with all the top leaders and hundreds of followers, was arrested. Many were charged under the Peace Preservation Law 治安維持法 and with lese-majeste. Omoto’s shrine in Kameoka was destroyed by dynamite, and all facilities in Ayabe and other locations were dismantled. Major media labeled Omoto as a cult. The crackdown was harsh, and almost anyone with any association to Omoto was affected. Some were reported to have become insane due to intense interrogation, and some died in prison by suicide. This incident became known as the Second Omoto Incident.

Morihei, due to his prominence within Omoto, was also subjected to questioning but ultimately received no punishment. This may have been due to his excellent connections among the nobility, military, and bureaucracy, with many of his students being prominent and respected figures. According to Morihei’s own account, his student Kenji Tomita 富田健治, commissioner of the Osaka Police, provided significant assistance during the incident.

Building (高天閣) destroyed in The Second Omoto Incident

After the crackdown, all of the religion’s activities were prohibited, and Omoto was practically outlawed, forced underground until after World War II. In 1942, the charges under the Peace Preservation Law against Omoto were dismissed, and Onisaburo was granted release on bail after being detained for six and a half years. The charge of lese-majeste was also dismissed following the abolition of the criminal code in 1947.

The Second Omoto Incident reflects a broader pattern of religious suppression in prewar Japan. It serves as a reminder of the limitations placed on freedom of religion during Japan’s militaristic period and underscores the tensions between traditional beliefs, state ideology, and emerging religious movements. After World War II, Omoto re-emerged, and Japan’s new constitution, which included freedom of religion, allowed it to reestablish itself legally.

Today, Omoto continues to exist as a small religious organization based in Kameoka, Kyoto Prefecture. Its activities now focus primarily on promoting peace initiatives, fostering interfaith dialogue, and preserving traditional cultural practices.

Related reading: The Rise of a New Religion That Shaped Aikido and Sparked the First Omoto Incident

Author’s Note: We appreciate your readership! This article serves as a preliminary introduction to the subject matter. While we aim for accuracy, we cannot guarantee the content’s precision and it may contain elements of speculation. We strongly advise you to pursue additional research if this topic piques your interest. Begin your AikidoDiscovery adventure! 🙂